5 Practical Tools and Material for Enhancing your Information Literacy Session

Creating Hands-on Assignments and Exercises for Learning Outcomes

After you have completed a basic needs assessment and have learning outcomes in mind for your session(s). We need to pause and focus briefly on your role as teacher. If you have time, in future, please read Parker Palmer’s, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life (1997). Below are some highlights from the book that are helpful.

Highlights from Parker Palmer’s, The Courage to Teach (1997)

- Good teaching cannot be reduced to technique. You may be looking for a ‘magic bullet’ or strategy for a perfect learning experience that works for all audiences. This does not exist. Focus on building a repertoire of teaching skills and don’t be afraid to experiment. Flexibility and continuous learning for both teachers and students is key.

- Good teachers possess a capacity for connectedness. Aloof teachers, especially librarians do more harm than good. Use your imagination and give all people the benefit of the doubt. Develop the mantra: I am here to help.

- Teaching is an exercise in vulnerability. Being vulnerable with your students helps to create connectedness. It is our insecurities as teachers that lead us to appear infallible. This doesn’t help our students. In the classroom, I often use times that I misspell words as a teaching experience. We all misspell words, how can that affect our search results?

- Do not be afraid of mentorship or mentoring others. The best way to become a better teacher is to watch those who are better at it than you. Ask them for their advice and to audit their classroom.

- Attitude is key. Don’t be afraid to express your true self in the classroom. Reveal your enthusiasm, interest, conviction, and self-confidence, it will be catching to your students.

Mindfulness-Based Tools

In recent years, several publications have explored the topic of mindfulness in library spaces. In The Mindful Librarian: Connecting the Practice of Mindfulness to Librarianship (2015), Moniz et al. explore mindfulness approaches that relate specifically to the challenges and varied tasks that librarians face, including the increase of work that accompanied the adoption of the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy.

In The 360 Librarian: A Framework for Integrating Mindfulness, Emotional Intelligence, and Critical Reflection in the Workplace (2019), Owens and Daul-Elhindi discuss the challenges that Moniz et al. (2015) do, but delve further into the unique political circumstances that academic librarians face as an organization within a larger organization. The “360 Framework” features 5 steps: 1. Mindful Practice, 2. Emotional Awareness, 3. Engaged Communication, 4. Empathetic Reflection and Action, and 5. Reassurance. Each step includes “practical activities, case studies, and essays by librarians.”

Recipes for Mindfulness in Your Library: Supporting Resilience and Community Engagement (Charney et al., 2019) details mindfulness programming, activities, and scholarship from across the United States, including: journaling to practice reflexive writing, mindfulness strategies for leadership, creating student destress zones, and using mindfulness to overcome research anxiety.

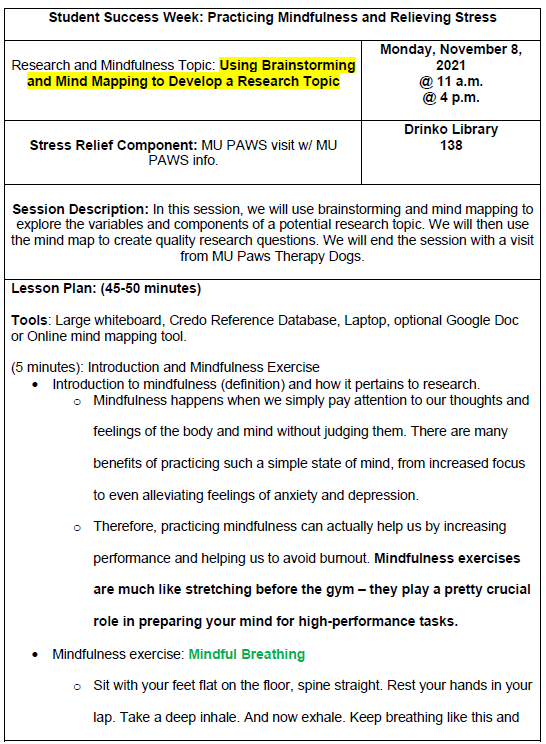

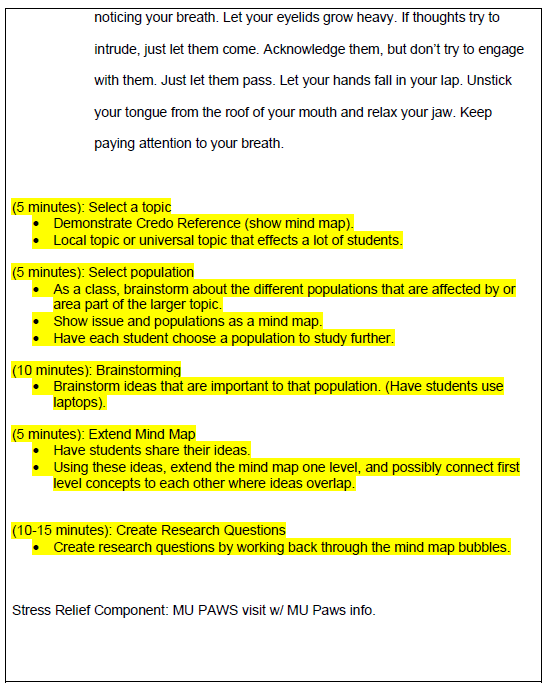

At Marshall University, we host a library stress relief week before finals each semester, host weekly yoga, and after returning to campus after the COVID-19 pandemic, held a week-long Student Success Week: Practicing Mindfulness and Relieving Stress event featuring adaptations of many of these activities, each with both a research and mindfulness component. The integration of mindfulness into library spaces developed, in part, due to feelings of burnout that librarians experience. Librarians noticed an overlap between mindfulness-driven practices and those we use to engage students in learning: reflexive writing, emotional awareness (If I Apply Source Evaluation), relieving (research) anxiety, and a need to cultivate a state of mind that is primed for discovery through a focus on being present.

Below is a description of all 5 sessions, with an example of one of these daily lesson plans: Others can be found in the back of this book.

Student Success Week 2021: Practicing Mindfulness and Relieving Stress

Research and Mindfulness Topic: Using Brainstorming and Mind Mapping to Develop a Research Topic

Mindfulness Exercise: Mindfulness Breathing

In this session, we will use brainstorming and mind mapping to explore the variables and components of a potential research topic. We will then use the mind map to create quality research questions

Stress Relief Week Component: MU PAWS visit w/ MU PAWS info.

Research and Mindfulness Topic: Mindfulness and the Research Process: Emotional Awareness, Overcoming Research Anxiety, and Understanding Bias

Mindfulness Exercise: Mindfulness Bell

In this session, we will practice mindfulness exercises, learn more about mindfully-performed research, and then apply it through hands-on practice, all geared toward reducing research anxiety. We will explore our feelings regarding controversial topics, learn strategies for relieving library-related anxiety, and explore the way that bias and emotions go hand in hand.

Stress Relief Week Component: DIY Stress Balls and Planning Page Handouts

Research and Mindfulness Topic: Mindful reflexive writing as a research strategy

Mindfulness Exercise: Mindful Observation Exercise

Learn how to become a more effective researcher by incorporating mindful, reflexive writing as research strategy. This session asks you to ask questions about what you know and also how you feel about the topic that you are engaging with. Students should come to the session with a topic in mind, preferably a topic that you are currently researching or completing an assignment about. By the end of the session, students will have a better understanding of the types of questions that they should ask when starting a research-based project.

Stress Relief Week Component: Yoga positions handout and Kacy Yoga recording link QR Code w/ Counseling Center info

Research and Mindfulness Topic: Scholarship as conversation: Discovering missing voices and viewpoints when researching

Mindfulness Exercise: Mindful Appreciation

In this session, you will gain an understanding of how the content of resources and the author’s point of view are essential to the research process. You will have a chance to reflect on whose voices are being included and why a wide variety of voices is imperative to enriching your research project and discuss strategies for finding and using sources that contain underrepresented voices.

Stress Relief Week Component: Coloring pages w/ coloring pencils and Stress Relief Guide QR Code.

Research and Mindfulness Topic: Mindfully evaluating resources

Mindfulness Exercise: Musical Mindfulness Exercise

IF I APPLY, the source evaluation tool developed at MU Libraries (by MU Research Librarians Eryn Roles and Sabrina Thomas and Penn State Librarian Kat Phillips), is one of the best mindfulness tools that you can have in your research arsenal! Learn why IF I APPLY can be viewed as an exercise in mindfulness and learn how to use it to evaluate resources for credibility.

Stress Relief Week Component: Virtual Scavenger Hunt QR Code and Virtual Escape Rooms QR Code, with library SWAG (highlighters, pens, candy)

SSW – Monday Lesson Plan – Using Brainstorming and Mind Mapping to Develop a Research Topic

Creating mindfulness-based tools for the classroom doesn’t have to be this complex or require this type of preplanning. Reflexive exercises allow us to assess our own teaching by reflecting on the state of our body and mind while we teach.

Classroom Mindfulness Exercise

Being mindful of your actions in the classroom is a way of sharpening your teaching skills. Below is a checklist for instructional awareness. The answers to these questions will help you answer the question of how well you are connecting with your students:

- What do you do with your hands?

- Where do you stand or sit?

- When do you move to a different location?

- Where do you move?

- Where do your eyes most often focus?

- What do you do when you finish one content segment and are ready to move onto the next?

- When do you speak louder/softer?

- When do you speak faster/slower?

- Do you laugh or smile in class?

- How do you use examples?

- How do you emphasize main points?

- What do you do when students are inattentive?

- Do you encourage student participation? How?

- How do you begin and end your sessions?

Time Allocation for Sessions

One-Shot

Best Practices for One-Shot Sessions

- Limit your one-shot to one learning outcome.

- At the very most two if it cannot be avoided

- When possible, tie the one-shot to an assignment.

- Students are far more invested in learning various literacy skills when they are actively required to use them.

- Be highly conscious of your time.

- As seen in the Mindfulness lesson plan above, you must make every minute count, and deviating from your schedule could mean that you don’t complete the lesson thus students don’t meet the learning outcoming.

- Engage with the students and catch their attention at the very beginning of class. Try to understand what motivates them and then incorporate it into the classroom.

- This can be the hardest best practice to figure out!

- A few easy Kahoot questions about research and the library.

- Play Four Corners to get to know students’ likes and dislikes (use Kahoot or have students physically move to each corner of the room); for example: Which is your favorite season? Favorite animal to keep as a pet? Favorite genre of music? Favorite place to go on vacation? Answer examples: A. Spring B. Summer C. Autumn D. Winter, A. Cat B. Dog C. Fish D. Rabbit, A. Rock B. Country C. Pop D. Classical, A. Large city B. Beach C. Mountains D. Countryside The trickiest part is that you must ask questions with at least 4 possible answers, but that don’t have so many possible answers that your audience doesn’t feel limited by 4.

- Ask students to share their research topics with you and use these topics in demonstrations. Students pay more attention when you are showing them specifically what they need.

- This can be the hardest best practice to figure out!

Embedded Sessions

Best Practices for Embedded Librarians

-

Cultivate a team relationship with the professor of the course by including them in all preparation.

- Discuss your plans for each session and let them know that you welcome their feedback.

- Limit yourself to one learning outcome per session.

- Just like a one-shot. Treat each session as a new opportunity to thoroughly teach one learning outcome.

- Give out clear instructions on information literacy assignments at the beginning of the first session in order to build motivation.

- Let students in on the process. Let them see how each session and assignment builds on their previous understanding.

- Make yourself available to the students for the entire course. You are their librarian for the entire semester, not just for the sessions.

- Give students your email address and office number. Show students how to schedule a research consultation with you or an appointment during office hours.

- Try to come to the first day of class for a brief introduction.

- This one can be difficult if your schedule doesn’t permit this, or the professor doesn’t have the available time to give up during their first class period.

- Alternatively, write an email to students introducing yourself, perhaps with a short video, and ask the professor to forward it to their students.

- This one can be difficult if your schedule doesn’t permit this, or the professor doesn’t have the available time to give up during their first class period.

Other Configurations

Watch the presentation below from the Library Instruction Tennessee 2024 conference on library instruction sessions beyond the traditional one-shot session.

LIT 2024 – Transformative Pedagogies: Rethinking Library Instruction Past One-Shot Sessions

Active Learning

Approaches to Adding Active Learning Activities to the Classroom

Examples of Active Learning Classroom Activities

- Clarification Pauses – This is a simple technique aimed at fostering “active listening”. Throughout a lecture, particularly after stating an important point or defining a key concept, stop, let it sink in, and then (after waiting a bit!) ask if anyone needs to have it clarified. Or, ask students to review their notes and ask questions on what they’ve written so far (University of Michigan Center for Research on Learning and Teaching).

- Writing Activities such as the “Minute Paper.” – At an appropriate point in the lecture, ask the students to take out a blank sheet of paper. Then, ask the topic or question you want students to address; for example, “Today, we discussed conductive heat transfer. List as many of the principal features of this process as you can remember. You have two minutes – go!” (University of Michigan Center for Research on Learning and Teaching)

- Self-Assessment – Students receive a quiz (typically ungraded) or a checklist of ideas to determine their understanding of the subject. Concept inventories or similar tools may be used at the beginning of the semester or the chapter for students to help students identify their misconceptions.

- Large Group Discussion – Students discuss a topic in class based on a reading, video, or a problem. The instructor may prepare a list of questions to facilitate the discussion.

- Think-Pair-Share – Have the students first work on a given problem individually, then compare their answers with a partner and synthesize a joint solution to share with the class.

- Cooperative Groups in Class (Informal Groups, Triad Groups, etc) – Pose a question on which each cooperative group will work while you circulate around the room answering questions, asking further questions and keeping the groups on task. After an appropriate time for group discussion, ask students to share their discussion points with the rest of the class.

- Peer Review – Students are asked to complete an individual homework assignment or short paper. On the day the assignment is due, students submit one copy to the instructor to be graded and one copy to their partner. Each student then takes their partner’s work and depending on the nature of the assignment gives critical feedback, corrects mistakes in problem-solving or grammar, and so forth.

- Group Evaluations – Similar to peer review, students may evaluate group presentations or documents to assess the quality of the content and delivery of information.

- Brainstorming – Introduce a topic or problem and then ask for student input. Give students a minute to write down their ideas, and then record them on the board. For example, “What are possible safety (environmental, quality control) problems we might encounter with the process unit we just designed? “ could be a brainstorming topic in an engineering class.

- Case Studies – Use real-life stories that describe what happened to a community, family, school, industry, or individual to prompt students to integrate their classroom knowledge with their knowledge of real-world situations, actions, and consequences.

- Active Review – Pose questions and the students work on them in groups. Then students are asked to show their solutions to the whole group and discuss any differences among the solutions proposed.

- Role Playing – Here students are asked to “act out” a part. In doing so, they get a better idea of the concepts and theories being discussed. Role-playing exercises can range from the simple (e.g., “What would you do if a client rejects your engineering design concept based on the cost and usability of the product?”) to the complex.

- Jigsaw Discussion – In this technique, a general topic is divided into smaller, interrelated pieces (e.g., the puzzle is divided into pieces). Each member of a team is assigned to read and become an expert on a different topic. After each person has become an expert on their piece of the puzzle, they teach the other team members about that puzzle piece. Finally, after each person has finished teaching, the puzzle has been reassembled and everyone in the team knows something important about every piece of the puzzle.

The University of Michigan’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching has a fantastic resource, “Active Learning Strategies: Reflecting on Your Practice,” for reflecting on and evaluating your use of active learning in your classrooms. Their resource asks you to rate your use of certain activities, categorizing them as low, medium, and high complexity. Along with discussing many of the active learning activities above, the University of Michigan’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching provides extensive resources on how to implement active learning and how to navigate challenges like class size and faculty concerns about techniques and technology.

Active Learning

Lesson Plans

Why create a lesson plan?

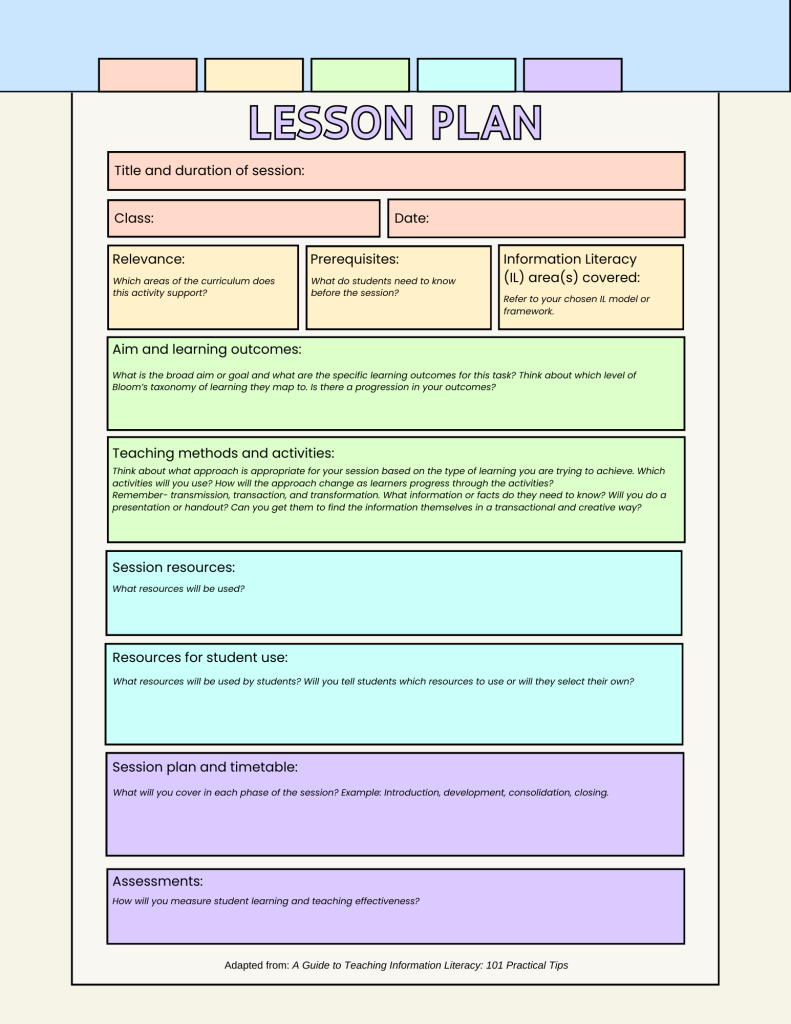

Lesson plans normally outline the aims and outcomes of the session, describe the learning activities to be used, and provide a timetable and structure for the instruction session. The plans are a valuable resource for you, but remember they can also be shared with colleagues who may teach the same session, provide a formal record of good practice, or be the basis of your teaching log.

There are several approaches to lesson planning. At the minimum level, a lesson plan need only be a basic timetable. More helpfully draw up a simple table.

Example

| Learning Outcome | Activity | Time | Material | Assessment |

| To be able to use a recognized referencing format (such as APA or MLA) to cite books, journals, websites, and other formats | Referencing exercise | 20 minutes | Samples of material

APA or MLA Citation Manual Student Worksheet |

Peer assessment using model answers. |

Lesson plans can be much more extensive (like the Mindfulness lesson plans above). In this format, they are commonly used by schoolteachers and there are many free lesson plans available on the internet (try the ERIC database or Guardian Teacher Network) Most school lesson plans will state how they relate to the curriculum This may not be as easy to define for information literacy tasks outside formal education, but you can cross-reference your leaning outcomes against one of the information literacy standards discussed in Part 1. If you can map your sessions to a curriculum or subject standard then this will help you promote the relevance of your teaching (if you are teaching to teachers and academics) Here is an example of a sample lesson plan adapted from Blanchett et al. (2011).

Lesson Plans and Activities for Online Learning

Lesson Plans and activities so far have focused on face-to-face information literacy instruction, but what about online teaching? There are similar best practices for quality assurance for information literacy modules for both distance learners and those individuals who simply cannot make it to a face-to-face class. Information literacy modules can be made in-house or purchased through companies such as Credo. Quality Matters (QM) is one common organization providing quality assurance to online learning through the use of research, rubrics, standards, peer review, and ongoing professional development; QM charges for certification and for access to their annotated standards, however, their nonannotated standards are available to view, and many educational organizations pay for certification; view the QM Higher Education Standards here. Most of the activities in this chapter can be adapted for use in an online or hybrid session.

When creating custom modules for your website or integration into a learning management platform, this LibGuide, “Active Learning Activities for Online Information Literacy Tutorials,” from Lindsey McLean at William H. Hannon Library is an invaluable resource. Additionally, McClean includes helpful resources for creating learning outcomes and a list of possible active learning activities that are tailored to online teaching and learning as well as a guide to creating online tutorials.

The following presentation from Elena Rodriguez at the Library Instruction Tennessee Conference in 2021 is a culmination of many of the topics discussed in this chapter. Rodriguez advocates for a mindful approach to designing online classroom spaces, one that fosters empathy, communication, patience, and compassion. Perhaps most impressive, Rodriguez was able to successfully implement her ideas in a one-credit hour, asynchronous library research elective course; her ability to engage her students and foster fruitful communication belies the distance and asynchronous nature of the course.

LIT 2021 – Compassionate Instruction: Building Support in Online Spaces

Chapter 5 Word Match

Information Literacy and Humor Discussion

Information Literacy and Humor Discussion (5 points)

Read Humor in library instruction: a narrative review with implications for the health sciences, by Elena Azadbakht.

https://doaj.org/article/748165df448f4ad8a467f4dc0ded4119

(If you are unable to access this article, please contact the instructor as soon as possible).

In an original post, discuss why you think it is important to keep your sense of humor while teaching information literacy. Have you ever had an instructor who lacked a sense of humor or was very dry? Compare that to an instructor who used humor in class. In which class did you retain more information? Why? What other ways do you think you could incorporate humor into a class? (Note: Use fictitious names and not real names in your post.)

Respond to at least two other students’ posts.

Evaluating Websites Activity Assignment

Evaluating Web Sites Activity Assignment (10 points)

Scenario: You are an instruction librarian at your local community college. As part of the broader English 101 curriculum requirement that emphasizes academic research, all freshmen community college students must attend one library session.

Task: You must create one hands-on group activity on how to evaluate websites. The learning objective for this 50 minute session is “Learners will demonstrate the ability to evaluate a website for credibility.” Your hands-on activity must include one worksheet and/or handout. Five points will be awarded for the activity description and five points for the worksheet and/or handout.

Please use the Marshall University Source Evaluation tool, IF I APPLY, created by Eryn Roles, Kat Phillips, and Sabrina Thomas, to complete this assignment. Use the handout below, and then review the “Think Questions” for each step of the evaluation process.

Reflection Questions

- Do you believe that mindfulness is compatible with instruction?

- Have you experienced the intersection between mindfulness and learning before?

- Compare the one-shot and embedded librarianship.

- Why might faculty/teachers prefer the one-shot session?

- Review your favorite active learning activity.

- Create a simple lesson plan showing how you would implement this activity with an audience of your choice.

a mental state achieved by focusing one's awareness on the present moment, while calmly acknowledging and accepting one's feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations, used as a therapeutic technique.

an educational approach in which teachers ask students to apply classroom content during instructional activities and to reflect on the actions they have taken.