4 Introduction to Planning Information Literacy Sessions: Developing and Teaching

The Beginning

Always Begin at the beginning, rooting your solution in understanding the complexities of the library and online services in the digital age.

Before the digital revolution in the late 20th century, research tasks were based solely on resources available in the library. Information-seeking was straightforward. The library had tools to locate information in print and media formats on hand. The library was a brick-and-mortar building that housed a collection in the strictest sense.

This collection was painstakingly selected by informed professionals with the developmental needs, domain knowledge, and language requirements of library users in mind. In such an environment, library users could assume the authority, accuracy, and truthfulness of many of the resources they use. With web-based information spaces, these assumed characteristics are gone.

Even the library as a mere warehouse of books is gone. Today’s library is highly diverse and not necessarily limited to a physical building. The proliferation and diversification of information is at once liberating and challenging. Avenues to assist users are easier to access; however, new challenges in programming and education abound. After an assessment of need, one should have a better understanding of who their target audience is and deficits in their information literacy skills. Librarians, especially teaching librarians must always remember that because of these dramatic changes, assumptions on behalf of our users must be checked and rechecked to tailor instruction to meet their needs.

User Needs

Teachers are challenged as never before to tailor instruction to meet the educational needs of a diverse population of learners. In order to do that we need to make sense of the differences in cognitive development and ability, cognitive style, social and cultural experiences and traditions, as well as language variations. Diagnosing instructional needs and customizing instructional approaches for information literacy requires flexibility and a willingness to continue to sharpen your teaching and presentation skills.

There are many ways to differentiate instruction. In the research literature of library and information science, individual differences have frequently been viewed in terms of ‘user needs’ and information-seeking behaviors. Within the educational literature, differences have been identified related to cognitive and personal development and learning styles. Research in sociology, communication, and other disciplines suggests worldview, culture, socioeconomic status, and gender as foundations of difference. Understanding each of these dimensions can help librarians design effective learning sessions. Pedagogies were discussed in depth in the first module. In the following paragraphs let’s look at ways to accommodate learning styles and capitalize on learning strengths to create information literacy sessions that are student-centered.

Reframing Research Questions

Collaboration

Learning-Centered Teaching (LCT)

Student-Led Learning

Learner-Centered Teaching

Traditional Teachers use words like: |

Learning-Centered Teachers use words like: |

| Teaching | Learning |

| Cover | Investigate/Explore |

| Inform | Facilitate |

| Present/Deliver | Experience/Interact |

| Facts | Ideas |

| Memorize | Relate/Understand |

| Replicate | Construct/Apply |

| Compete | Cooperate/Collaborate |

| Grades | Improvement |

Strategies for Multidimensional Student-Centered Learning

- Provide formal and informal seating.

- Vary the lighting from bright to subdued.

- Provide quiet and noisy spaces.

Emotional:

- Expect responsible behavior in the completion of tasks. Make learning activities relevant to the learners’ interests and concerns.

- Express confidence in student ability.

- Provide positive feedback and support.

- Plan for both individual and small group work

- Use same-sex groupings where cultural asymmetry related to gender hampers the development of information-seeking and computer skills.

- Explain and negotiate instructional strategies when cultural differences in approach prove problematic.

- Interact with students as they work on projects.

- Be sensitive to stylistic differences in behavior.

- Provide research topics that are racially and ethnically inclusive.

- Invite community speakers/local libraries to visit the library to speak when applicable.

- Allow for activity as well as reflection.

- Provide interactional activities as well as written activities. Take account of energy levels of students.

- Vary activities and include some break time.

- Ground new learning in what students already know.

- Explain tasks in advance and provide an overview

- Divide complex tasks into smaller, sequential steps

- Provide oral and visual as well as written instructions.

- Use modeling, demonstrating, and role-playing in explaining activities.

- Provide multisensory approaches to learning.

- Provide activities that encourage exploration and challenge thinking

- Provide structured and unstructured alternatives to the same assignment.

- Where appropriate, emphasize collegiality over authority.

- Provide choices of projects, resources, activities, and equipment.

- Include time for both classroom discussion and reflection.

Working from Course Objectives to Outcomes

Successful Learning Outcomes

What makes for a successful learning outcome?

A successful learning outcome is:

- measurable (judgeable)

- clear to learners and stakeholders

- integrated, developmental, transferable

- uses ACRL Frameworks and Standards as a basis, not an end

- matches the level of the learner and matches the session time frame

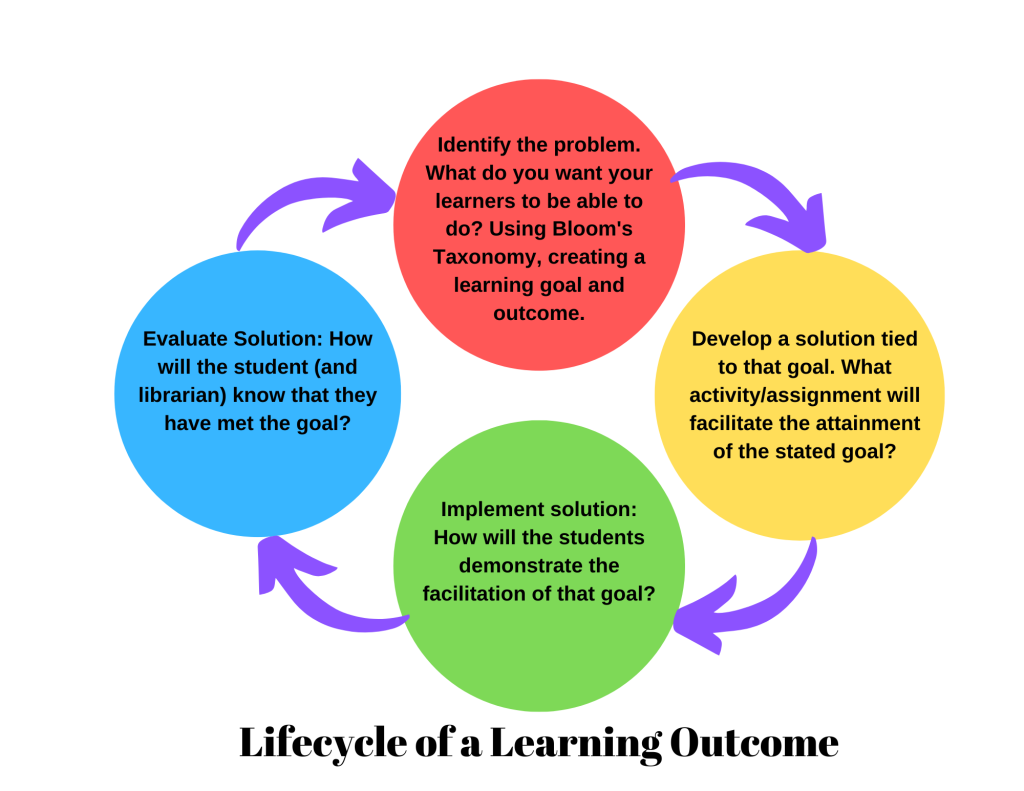

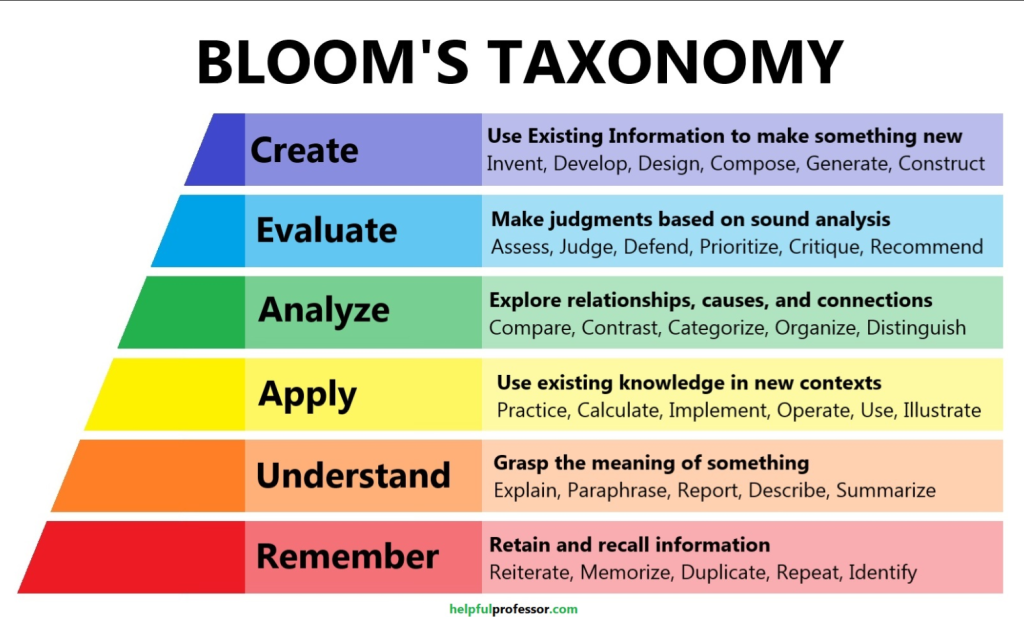

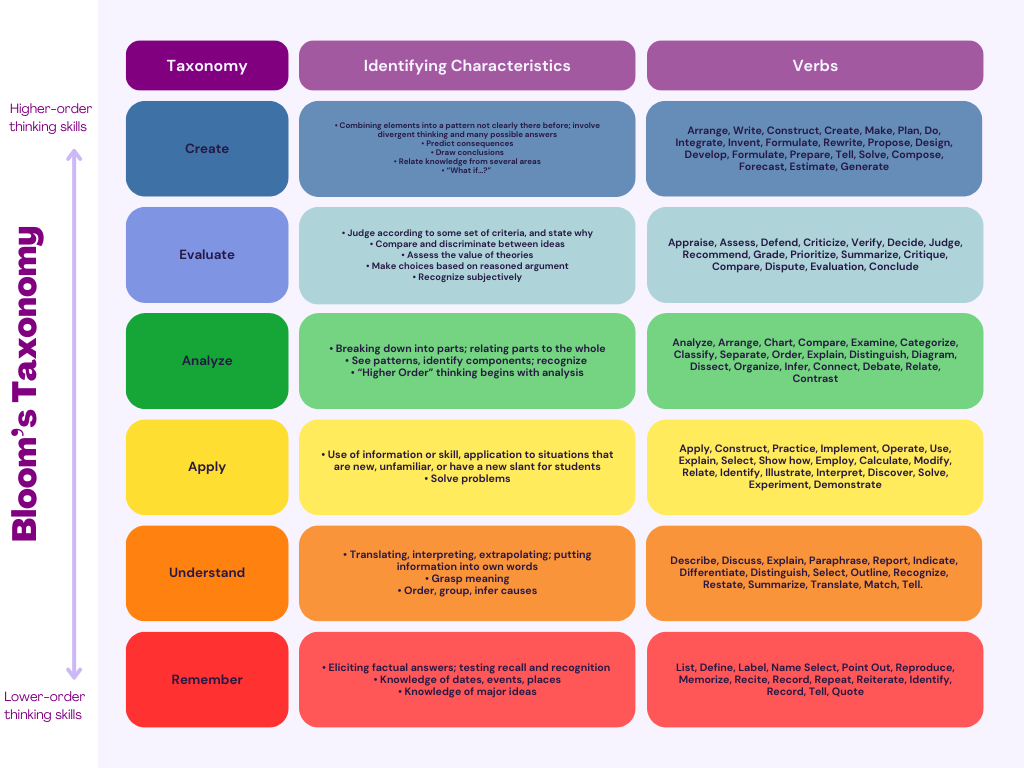

- uses a variety of levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy for Writing Outcomes

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom proposed a framework for classifying learning outcomes and skills. Lupkowski and Martin (2007), say that “Bloom’s Taxonomy classifies cognitive behaviors according to a hierarchy of domains, providing a framework for viewing the educational process, classifying goals of the educational system, and specifying objectives for learning experiences.”

Real-world Application

Putting This Into Practice in the Real World

Target Audience: freshman high school students

English Course Objective: Student-created research papers on a topic of their choosing.

The librarian, after conducting a needs assessment, identified an information literacy deficiency, the use of credible resources for research paper.

In a 50-minute session, the librarian’s learning objective for the class is: Students will identify qualities that, when combined and viewed as a whole, signify that a website or other web resource is credible. (Note: In a 50-minute session, librarians should try not to cover more than two learning objectives.)

The ABCD Model

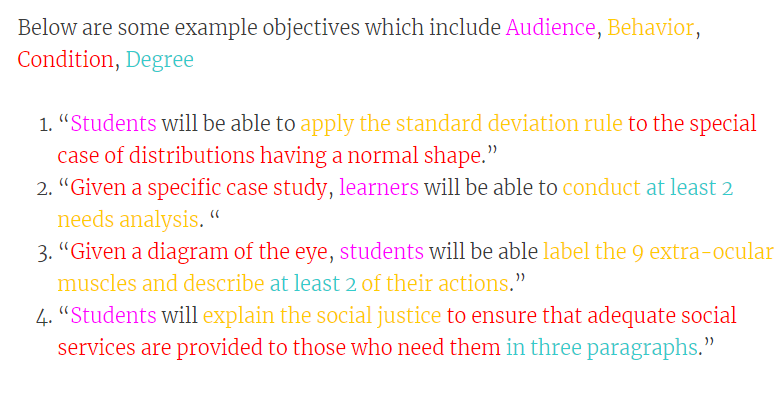

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a basis, the ABCD Model, Kurt (2020), helps us “to create clear and effective objectives. It consists of four key elements: (A) Audience, (B) Behavior, (C) Condition, and (D) Degree.

A-Audience: Determine who will achieve the objective.

B-Behavior: Use action verbs (Bloom’s taxonomy) to write observable and measurable behavior that shows mastery of the objective.

AD

C-Condition: If any, state the condition under which behavior is to be performed. (Optional)

D-Degree: If possible, state the criterion for acceptable performance, speed, accuracy, quality, etc. (Optional)”

Example:

Chapter 4 Assessments

Learning Activities Brainstorming Self Assessment

Chapter 4 Quiz

Reflection Questions

- What are your thoughts on Learning-Centered Teaching?

- Have you experienced LCT in your educational career?

- Review the Lifecycle of a Learning Outcome graphic.

- Why it is a cycle?

- Why would you need to assess the problem after evaluating a solution?

- Review the Bloom’s Taxonomy chart.

- Develop one simple goal/outcome with an appropriate activity for each level.

Introduction to Information Literacies Assignment

Introduction to Information Literacies Assignment (10 points)

Scenario: As the new instruction librarian at Huntington High School, you have been selected to give a brief ten-minute presentation to the Board of Education on information literacy.

Task: You will build a PowerPoint presentation entitled, “Introduction to Information Literacy.” Your presentation’s goal is to inform the Board of the importance of information literacy and to demonstrate its importance to high school students’ education. Your presentation must include:

- Who coined the term information literacy?

- What is information literacy?

- When is information literacy useful?

- Why is information literacy important?

- How does information literacy help to create lifelong learners?

Your presentation should include a title slide, at least one slide for each of the questions above, and a slide for your references (APA Citation Style).

a set of beliefs or a way of thinking about teaching itself with special emphasis on how we interact with our learners

A learning objective is a statement that captures specifically what knowledge, skills, and attitudes your learners should be able to exhibit following instruction