10 Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?”

In This Chapter

Author Background

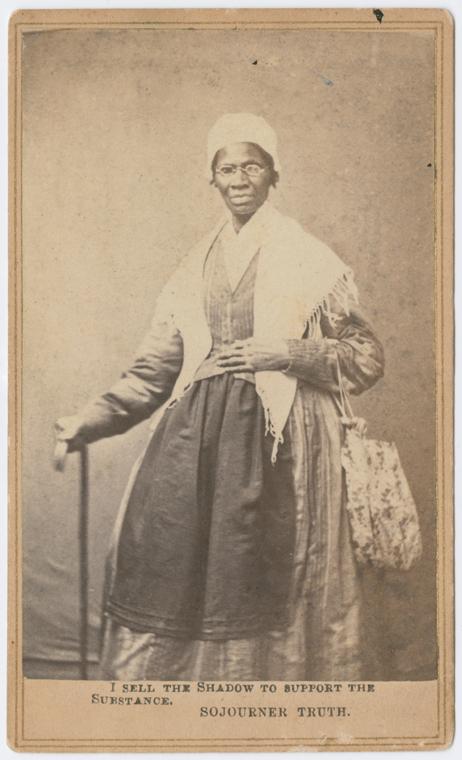

Born into slavery in 1797, Isabella Baumfree, who later changed her name to Sojourner Truth, would become one of the most powerful advocates for human rights in the nineteenth century. Her early childhood was spent on a New York estate owned by a Dutch American named Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh. Like other slaves, she experienced the miseries of being sold and was cruelly beaten and mistreated. Around 1815, she fell in love with a fellow slave named Robert, but they were forced apart by Robert’s master. Isabella was instead forced to marry a slave named Thomas, with whom she had five children.

Abolition Involvement

In 1827, after her master failed to honor his promise to free her or to uphold the New York Anti-Slavery Law of 1827, Isabella ran away, or, as she later informed her master, “I did not run away, I walked away by daylight….” After experiencing a religious conversion, Isabella became an itinerant preacher and in 1843 changed her name to Sojourner Truth. During this period, she became involved in the growing antislavery movement, and by the 1850s, she was involved in the women’s rights movement as well. At the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention held in Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth delivered what is now recognized as one of the most famous abolitionist and women’s rights speeches in American history, “Ain’t I a Woman?” She continued to speak out for the rights of African Americans and women during and after the Civil War. Sojourner Truth died in Battle Creek, Michigan, in 1883.

“Ain’t I a Woman”

Delivered in 1851 at the Women’s Rights Convention

Old Stone Church , Akron, Ohio

Copyright: Public Domain

Version 1

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ‘twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man – when I could get it – and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? [member of audience whispers, “intellect”] That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negroes’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back , and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain’t got nothing more to say.

Version 2

Wall, chilern, whar dar is so much racket dar must be somethin’ out o’ kilter. I tink dat ‘twixt de niggers of de Souf and de womin at de Norf, all talkin’ ’bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all dis here talkin’ ’bout?

“Dat man ober dar say dat womin needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted ober ditches, and to hab de best place everywhar. Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gibs me any best place!” And raising herself to her full height, and her voice to a pitch like rolling thunder, she asked. “And a’n’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! (and she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing her tremendous muscular power). I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And a’n’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear de lash as well! And a’n’t, I a woman? I have borne thirteen chilern, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And a’n’t I a woman?

“Den dey talks ’bout dis ting in de head; what dis dey call it?” (“Intellect,” whispered some one near.) “Dat’s it, honey. What’s dat got to do wid womin’s rights or nigger’s rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yourn holds a quart, wouldn’t ye be mean not to let me have my little half-measure full?” And she pointed her significant finger, and sent a keen glance at the minister who had made the argument. The cheering was long and loud.

“Den dat little man in black dar, he say women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wan’t a woman! Whar did your Christ come from?” Rolling thunder couldn’t have stilled that crowd, as did those deep, wonderful tones, as she stood there with outstretched arms and eyes of fire. Raising her voice still louder, she repeated, “Whar did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothin’ to do wid Him.” Oh, what a rebuke that was to that little man.

Turning again to another objector, she took up the defense of Mother Eve. I can not follow her through it all. It was pointed, and witty, and solemn; eliciting at almost every sentence deafening applause; and she ended by asserting: “If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women togedder (and she glanced her eye over the platform) ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now dey is asking to do it, de men better let ’em.” Long-continued cheering greeted this. “‘Bleeged to ye for hearin’ on me, and now ole Sojourner han’t got nothin’ more to say.

Answer the following true or false questions about the author and selection.

- What is the central message of Sojourner Truth’s speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” How does she challenge prevailing notions of gender and race during her time?

- How does Truth use rhetorical devices, such as repetition and parallelism, to emphasize her points and engage her audience? What effect do these rhetorical techniques have on the overall impact of her speech?

- Discuss the historical context in which Sojourner Truth delivered her speech. How do the themes and arguments she presents relate to the abolitionist movement and the fight for women’s rights in the mid-19th century?

- In her speech, Truth highlights the physical and emotional strength of women. How does she counter prevailing stereotypes about women’s supposed frailty and inferiority? What examples and personal experiences does she provide to support her claims?

- Explore the intersectionality of race and gender in Truth’s speech. How does she address the unique struggles and discrimination faced by Black women? How does she argue for the inclusion and recognition of Black women’s rights within the broader women’s rights movement?

- Reflect on the impact of Truth’s speech during her time and its enduring legacy. How did her powerful words challenge societal norms and contribute to the fight for equality? How is “Ain’t I a Woman?” remembered and celebrated today?

- Compare and contrast Sojourner Truth’s speech with other feminist texts or speeches from the same era. How do her arguments and approaches align or differ from those of other women’s rights activists of the time, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton or Susan B. Anthony?

- Consider the language and style used by Truth in her speech. How does her use of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and her direct, impassioned delivery contribute to the impact of her message?

- How has “Ain’t I a Woman?” influenced contemporary discussions on feminism and intersectionality? In what ways are Truth’s arguments still relevant today, and are there any aspects that require further exploration or critique?

- Discuss the importance of Sojourner Truth as a historical figure and advocate for women’s rights and racial justice. What challenges might she have faced as a Black woman speaking out against gender and racial inequalities during a time of significant social and political turmoil?

Sources

“Sojourner Truth: Ain’t I A Woman?”, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/sojourner-truth.htm, Public Domain.

Truth, Sojourner. “Ain’t I A Woman?” Women’s Rights Convention, Anti-Slavery Bugle, June 21, 1851, page 160, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83035487/1851-06-21/ed-1/seq-4/, Public Domain.